Paddy is the largest crop cultivated across all the regions and seasons in India. With the Green Revolution, the paddy crop has become a commercial crop profile.

With over 46 million hectares (mha) of cropped area, the income from paddy cultivation becomes an important livelihood for the majority of farmers. However, the export ban on non-basmati white rice and 20 per cent export duty on parboiled rice introduced in the second half of 2023 has hit the paddy farmers hard.

So Shouldn’t the paddy farmers be compensated for the losses they have suffered due to the export ban?

Trends in rice cultivation

Since Green Reovlution, the area under paddy cultivation has increase exponentially. From 35 mha in 1964-65, the are under paddy has increased to about 46 mha in 2021-22, a 31 per cent rise.

The share of paddy in the total foodgrains area also increased from about 31 per cent to 36 per cent during the same period. Under the Green Revolution package the increased adoption of HVY seed and fertiliser in the irrigated area has increased the productivity and production of paddy.

While the productivity of paddy increased from 1078 kg/ha to 2809 kg/ha, the production has increased from about 39 million tonnes (mt) to over 130 mt during this period. Paddy alone contributed about 41 per cent to the total foodgrains production in 2021-22.

Along with Green Revolution, the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for paddy too has altered its cultivation scenario in the States.

Traditionally, paddy was predominantly cultivated in West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and Assam. Punjab was not an important State in paddy cultivation in the sixties and seventies. From 2.85 lakh hectares in 1966-67, paddy cultivation in Punjab zoomed to 29.78 lakh hectares in 2021-22, a 10-fold rise. This kind of increase has not been seen in any State since independence.

That said, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Telangana, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and Assam together accounted for about 77 per cent of India’s paddy area in 2021-22.

Shrinking profitability

A section of policymakers and economists believe that paddy farmers are making handsome profits. Is this correct?

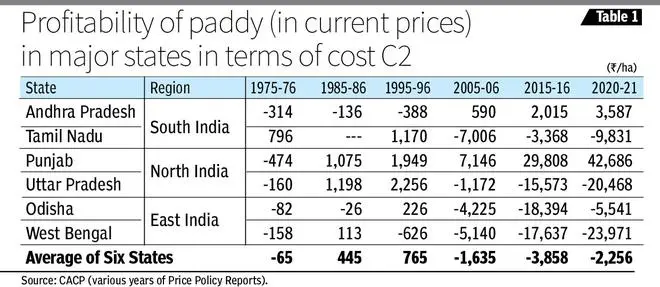

An analysis of the cost of cultivation data published by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) covering six important paddy-growing States, representing the northern-region (Punjab and Uttar Pradesh), eastern-region (Odisha and West Bengal) and southern-region (Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu), reveals the ptiable conditions of paddy farmers.

Many economists compute the profitability of crop in terms of cost A2 or cost A2+FL (all actual expenses in cash and kind incurred in production by owner plus rent paid for leased land plus imputed family labour cost), which does not capture the entire cost incurred by the farmers.

This analysis uses cost C2, which includes all paid-out costs, the imputed value of family labour, rent on leased land plus depreciation value of the fixed investment. The analysis shows that except for Punjab, paddy farmers in all the other five States have incurred heavy losses or reaped less profit at current prices over time (Table 1).

The profit from paddy cultivation in Punjab has massively increased from ₹474/ha in 1975-76 to ₹42,686/ha in 2020-21 because of the increased procurement level with MSP.

The average of all six important paddy-growing States shows that the losses incurred by the farmers have increased from ₹65/ha to ₹2,256/ha during this period. Shockingly, the analysis carried out for the period from 1971-72 and 2020-21 shows that the farmers from Tamil Nadu were able to earn profits only in 24 out of the 34 years for which data was available. A similar trend was observed in other States too.

So why are farmers unable to earn profits despite increase in paddy productivity? There are two main reasons for this.

First, due to rapid increase in inputs cost such as labour, fertiliser, seed, etc., the cost of cultivation per hectare has increased at a much faster rate than that of the Value of Output (VOP) realised from the crop, which is hitting the profitablity of the farmer.

For instance, the average worked out for the six paddy growing states shows that the cost C2 increased by 65 times between 1971-72 and 2020-21, whereas VOP increased only by about 59 times.

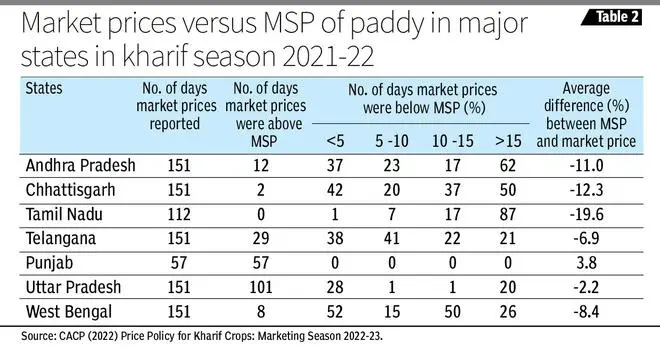

Second, though the government has substantially increased MSP for paddy during the last 10 years, farmers are not able to fully benefit from it due to poor procurement by state agencies. The farmers are forced to sell their produce in the open market where the price of paddy is always lower than the MSP, which is also reinforced by the data published by CACP (Table 2).

Evidence clearly shows that the paddy is not profitable to farmers. No doubt, the export ban on non-basmati white rice will deter the market price, forcing the farmers to incur more losses. Though the increased cultivation of paddy (a water-intensive crop) under the conventional flood method of irrigation is not desirable for countries like India because of looming water scarcity, we need to protect the paddy growers till alternative options are found.

Therefore, the government should provide adhoc compensation (taking into account the international market price of paddy) to the farmers for the losses that they might incur due to export restrictions. Alternatively, the government can increase the procurement level of paddy when an export ban is imposed so that the farmers will be able to avail the benefit of MSP.

The writer is former full-time Member (Official), Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices, New Delhi. Views expressed are personal